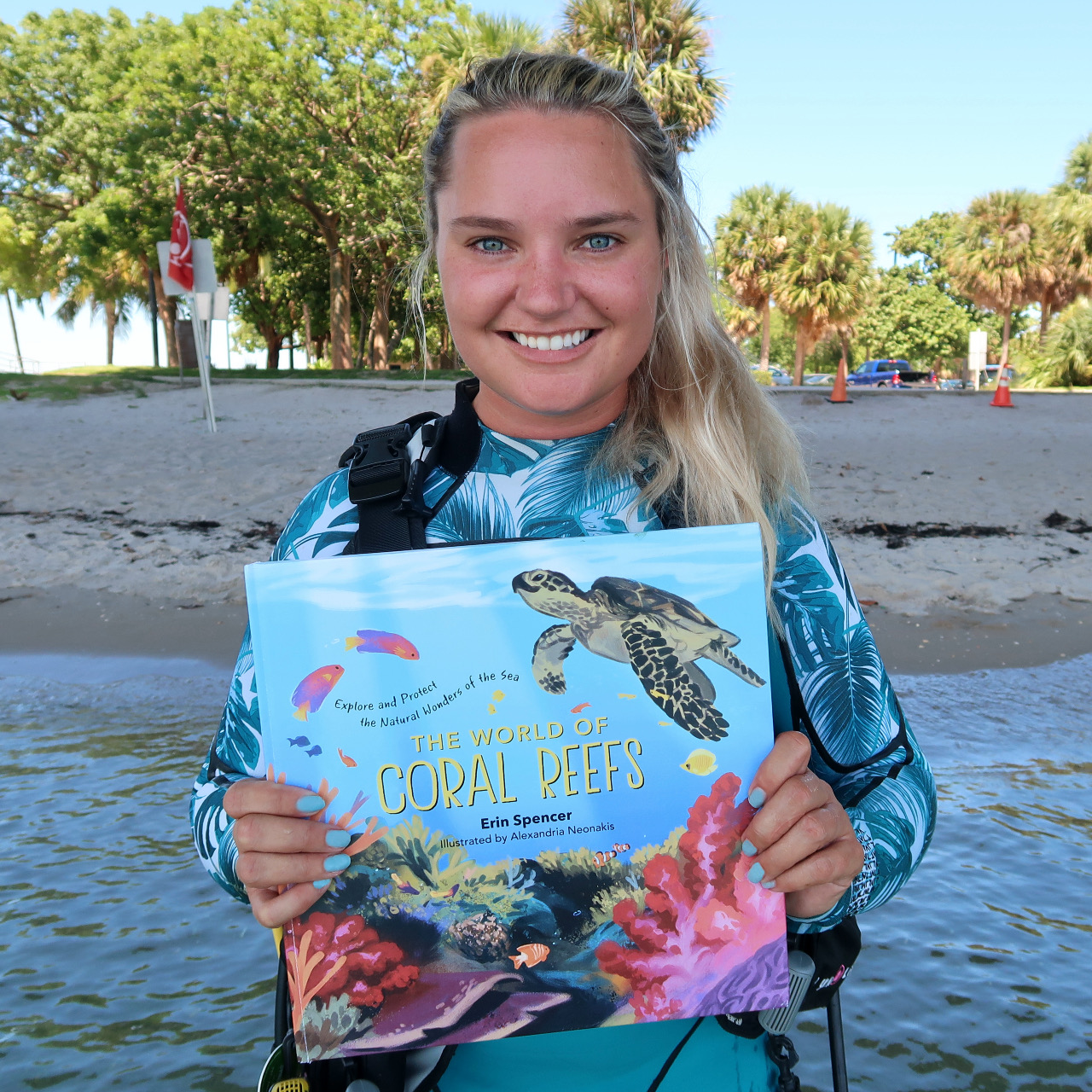

Meet Erin Spencer

I am a science writer, marine ecologist and Ph.D. candidate in Biology at Florida International University studying great hammerhead sharks. My research uses biologgers, or animal-mounted data collecting devices, to record acceleration, speed, depth, and more, which helps us understand shark energy needs and movement patterns. Prior to working in Florida, I received a Masters in Ecology from the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill where I studied red snapper fishery management and seafood mislabeling, and a Bachelors in Ecology from the College of William and Mary where I studied invasive lionfish management. I am a three-time National Geographic Explorer grantee and have given talks to groups of all ages through National Geographic, the World Bank, and TEDx, as well as many school groups. I am also an avid writer, and have a children’s book called The World of Coral Reefs that was published in March 2022. See more on my website at www.erintspencer.com and on Twitter at @etspencer.

2019 M.S. Ecology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

2014 B.S. Ecology, William & Mary

Get To Know Erin

I’m originally from Maryland and grew up in a rural area outside of Baltimore. I spent a lot of time outside poking around in the woods and farms, which helped me fall in love with nature. My family and I would also go to the Jersey Shore every summer, which was my first exposure to the ocean!

Definitely the blue ringed octopus. They are so small, about the size of a golf ball, and are one of the most venomous animals on the planet. Plus, they have gorgeous blue rings all over their bodies (hence the name), warning predators to leave them alone.

I study the movement and behavior of great hammerhead sharks. I use biologgers, or animal-mounted data collecting devices, to record speed, acceleration, depth, temperature, and more as the animal swims through the ocean. It’s essentially a Fitbit for sharks! These tags stay on for 24-48 hours, after which they pop up to the surface for us to recover. This data helps us understand their movement patterns and make predictions about how much food they need to consume throughout the day.

Great hammerheads are some of the most well-recognized animals in the ocean, but there is still a lot we don’t know about their basic biology. By understanding how they move and use energy, we can make predictions about their hunting activity and caloric needs, and how those things relate to temperature. This is especially important as the ocean warms and animals are affected by changing temperatures. I want to use this data to expand our knowledge of great hammerheads and help predict how they will respond to climate change conditions.

I’ve had a few career twists and turns, but I wouldn’t change a thing! After I graduated undergrad I worked in Washington, D.C., at National Geographic and Ocean Conservancy, where I did a lot of writing, web production, and social media. During that time I also did some research in Florida and in Fiji funded through National Geographic, which was an incredible way to gain experience in field work. I went to UNC-Chapel Hill to get my Masters in Ecology, hoping to return to D.C. to work in fisheries policy. While there, I decided I hadn’t had enough field work. So, I pursued my PhD at Florida International University, which is where I am now.

Every day looks very different, which is often great, sometimes chaotic. I spend a lot of time reading papers, applying for research funding, and writing code for my analysis. There’s more time behind a desk than you might expect. But I also do a lot of field research, which involves prepping the fishing gear and tags, then spending long days on the boat fishing for sharks. The conditions can be variable, so you need to be ready for anything. Fortunately, I work alongside many awesome colleagues–it’s easier to kill time on the boat when you’re on it with friends.

We can learn so much from these biologging data sets–each one tells us something significant about how great hammerheads behave in their environment. But there are a lot of things that have to go right to acquire one–sometimes it feels like the stars need to align just to get one data set. It’s incredibly rewarding when we’ve retrieved the tag, the data looks good, and I run it through the code. I get so excited to dive into the analysis! But troubleshooting our equipment and managing the logistics of getting out on the water is the most challenging part.

I’ve always loved writing and speaking about the ocean–I’ve published more than 130 articles on weird and wild ocean animals through Ocean Conservancy, and spoken to many classrooms through Skype a Scientist and National Geographic Classrooms. What always amazes me is how much young kids can understand pretty advanced science concepts. When writing this book, I wanted to create a captivating nonfiction book for young kids that didn’t skimp on the science. The illustrations were done by the incredibly talented Alexandria Neonakis, who really brings the entire book to life.

I spend a lot of my “free time” writing, but I don’t think that really counts! When I’m not working, I love to read, and go through a lot of nonfiction. I also like exploring Miami, where I live with my husband, dog, and three cats. We spend a lot of time trying new restaurants or walking the dog in new neighborhoods. I love Florida, and we never run out of things to try!

My biggest piece of advice is to not hold yourself back. It’s too easy to say, “oh I haven’t learned how to do that, and therefore I can’t do it.” Instead, try to think, “I haven’t learned how to do that yet, but I will.” I didn’t come into my PhD knowing how to use biologgers or handle large sharks, but I learned! It will take time, and a lot of patience, but if you put in the time you can learn anything. Have confidence that you can learn new things, and allow yourself the time and patience to try.

Interview conducted in May 2022